This essay first appeared, in a slightly less finished form, in Canvas. I sat on it awhile before posting.

Horror has been called the most moral of the genres, perhaps because it deals in calamity, in inexorable events and the experiences of small human victims, witnesses, collaborators. Because human existence is prone to repeated visitations from monstrosity in the shape of war, disease, and natural disasters, we have deep feelings about these things, and some of those feelings are about appeasement, and come from the same instinct that prompts us to pray.

If asked, most of us could make a list of things we know the characters in horror film and novels should avoid doing – or being, as in the case of the unchaste blond girl. Joss Whedon’s Cabin in the Woods plays with all those expectations and, at the same time, makes them the guiding evil secret behind the fate of everyone in the story (the great gods of chaos are being appeased by ritual sacrifices where the rituals are a series of variations on horror narratives. The hero, whore, fool, and virgin are what the sacrifice requires; human stand-ins for story). Whedon really gets the connection between horror stories and our deep instinct for appeasement. I began by wanting to write a horror novel partly for the simple challenge of trying for effects that would inspire fear. That urge was enough to give me a seventy pages of mayhem (which survive, radically altered in tone), but it wasn’t enough for a novel. In the end I persisted in writing Wake because horror was personally useful to me, because horror stories are about helplessness, and our feeble efforts to make ourselves safe, and about doing the right thing in the face of narrowing choices.

In the best horror stories, in the end, the danger for the heroes isn’t death, it’s doing the wrong thing by others, somehow failing that final companion who makes the experience bearable, and surviving it sustainable. Because a sole survivor hasn’t any other witnesses. No one to agree, ‘Yes, that happened.’ The sole survivor has the burden of explaining themselves, and never being fully understood. So, in horror stories, the most valuable life is that of the last person to die (because there’s usually a survivor). Horror stories are also about madness. How to respond to a world that is behaving in an utterly unreasonable way. A world where what was merely material and accidental suddenly seems to have sinister significances, traps and portents, and behind that maybe even a scheming and malevolent intelligence. (If you’ve ever tried to reason with someone in the throes of paranoid psychosis, all this will make real terrifying sense. And I’ll admit this much, I was writing about this because it was near to me and I had to deal with it, think about it, be responsible).

I started writing a horror novel for reasons of dread a little mysterious to me then, and as an exercise in seeing whether I could scare my readers. I continued writing because it was a very suitable way of talking about calamity, and how we cope — because of actual, biographical calamities, and having to cope. And I chose the non-realist mode because that’s what I do, and because of a deep aversion to a what is sometimes termed ‘catastrophe porn’: a sub-genre of that crypto-genre literary fiction. Catastrophe porn is a term sometimes used to characterise books that get their dignity from being ‘about’ real historical atrocities: wars, massacres, genocides. These are books written not by survivors or their children, but by authors for whatever reason wanting to grapple the world’s acknowledged serious matters.

I’ve alway been a little suspicious of writers who claim to be ‘using’ genre as a way of doing something more mannerly than actually writing a thriller or science fiction book or whatever. I don’t ‘use’ genre or ‘adopt its tropes’. I write as I read. I am in this corner with the Portal gun, and I can make a hole in the world and come out anywhere. Literature can appear in any genre – and I’ve often thought the literary works in genre are particularly delightful because they’ve discovered their own voice by finding their own orbit between competing gravities. It is often a voice with a flavour of freedom, and sly charm, and friendliness. When you hear it you feel that the writer is sitting down at the reader’s table. Raymond Chandler, Stephen King, Robert Louis Stevenson, Georgette Heyer; Ray Bradbury – all have this in spades. They are very attractive writerly personalities to be in the presence of.

The morality in horror stories is often punitive and conservative – if you don’t stay home you’re punished; if you’re a loose woman you’re punished; if you don’t respect other’s beliefs, you’re punished; if you don’t respect the story, you’re punished. Because of this, horror can be the most misanthropic genre. But what I had set myself to do was write a people-loving horror novel. The threats were going to be inhuman, for openers, but my story wasn’t going to be pitiless towards human failings. Nor was it going to reward virtue – except in the sense that some of the characters do work out that the last hope they have left to them was to not let others down. My horror novel was explore the heroism of stoicism, honour, and valour – all of which may seem remote as stated values, and old-fashioned. But, you see, I’d been watching these very things sustain my mother through the loss of her power of speech, of her strength, her mobility, her sense of taste and smell, her eyesight, her ability to breathe. And, in the end, if Mum hadn’t been treated with such tender sympathy by her grossly underpaid caregivers she would even have lost her dignity. So, for instance, when Mum was diagnosed the doctors had said -had promised – that she’d keep her bowel and bladder control. That, and that she’d be alert, intelligent, and herself right up to the end. They were right about the second thing, but not the first. Motor Neurone Disease attacks the control of voluntary muscles first, then the involuntary (it is paralysis of the diaphragm that kills its longest surviving sufferers). The gut has involuntary muscles. Peristalsis is involuntary. But the rectum is a voluntary muscle, and, in the end, Mum wasn’t able to control hers. The point I’m making here is how everyday and unexceptional horrifying things actually are. My characters in Wake, baffled by how little they can do for themselves and each other, and by how sequestered with their trials they are, with no rescue on hand, are just me. They are just us. And it is my observation that many people faced with tough shit, cope bravely.

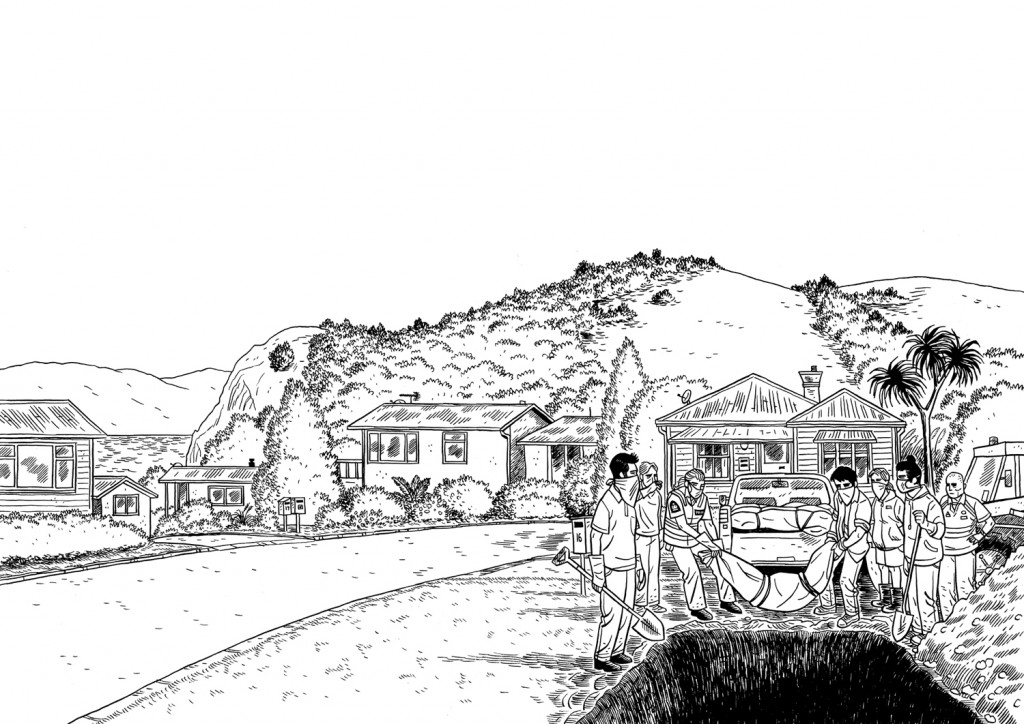

But there are many ways to fail – and in my novel the failures were never going to be the archetypical horror story’s fatal errors of too little chastity or too much curiosity, they were going to be real-world failings, some of which are the dark side of virtues – like an exclusive and inflexible devotion to a regimen whose aim is bodily perfection. This is the kind of loose thread of a person’s character that the novel’s monster picks and pulls at. This is the threat – delusion, solipsism, selfishness, cowardice, despair. And that isn’t to say that the monster and its acts are allegorical. It’s a real monster. (All monsters are real, like all angels are terrible.) The things that were scaring me were psychoses in people near to me, the fatal offhand malice of the man who killed my brother-in-law, and my mother’s terrible disease. That, and my own shrinking inadequacy in the face of it all. Real things and feelings just then best expressed as horror – as mad acts, bloodshed, being trapped, having no help, having crushing responsibility, and the gradual closing down of all means of doing any good.