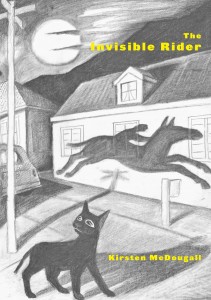

I was pleased and privileged yesterday to launch this book at the Thistle Hall in Wellington. This is my launch speech.

I was fortunate to be present at the birth of Philip Fetch. It was during a workshop on world-building that my sister Sara and I ran on four consecutive Saturdays a few years back. The workshop group figured out between themselves a plot germ, and a collection of character germs. These characters were put in a hat and everybody in the workshop picked one. (Sara’s and my plan was to try to shake the writers free of any cherished avatars or Mary-Sue characters they might have brought with them into the room.) The person Kirsten pulled out of the hat was one half of a couple who ran a garden centre. The writer who got the other half of the garden-centre couple wasn’t particularly happy to lose the beautiful young mistress of a bondage and discipline loving super-rich CEO–the character she’d brought into the room and which she really probably should have carried off again and developed! Anyway–though she wasn’t happy, for Kirsten this early-middle-aged fellow she’d had wished on her was a very happy accident. None of us–Sara, me, the group–had any idea what the character was like. A bloke, thirty-something, that was all we had. But when, the following Saturday, Kirsten produced her piece of writing she came up with an unusual and authentic voice, and a fully formed worldview. It was like magic. And Philip was what Kirsten carried away from that world-building workshop. Some time–and baby Francis– later I got to read the manuscript of The Invisible Rider. And to meet the true and final Philip Fetch.

Philip is a husband, to Marilyn, the father of a young family, George and Charlie, a lawyer with an office in the local mall, who handles conveyancing, property, wills, the occasional divorce–those little bits of road, and bridges, and driveway in an ordinary life. He is a man who believes that cycling to work is a good thing–though he doesn’t do it often enough. He’s a man who isn’t so much keen on exercise, or self-improvement, as someone who likes to commune with the wind, and have a bit of time to himself to think. He’s a particular man, a well-intentioned man, someone who would like to save the planet, be a better husband, be a better father, a better friend. He has, like most of us, a feeling for how things should be. The shape of a good life. But he’s frequently baffled, and better suited to acts of wish than acts of will. Though his wishes are very powerful. “I won’t die. You won’t die. You will never, ever have to make your own dinner” he thinks, in desperate benediction, at one of his children.

The Invisible Rider is a discontinuous narrative–a wonderful and under-explored form, somewhere between a collection of stories, and a novel. (The Invisible Rider‘s illustrious predecessor in New Zealand writing is, of course, Barbara Anderson’s brilliant Girls High.) In these stories–or chapters–nothing plays out the way the reader expects. Kirsten’s imagination is social, socially observant–for instance she notices the way that people disavow things they supposedly approve of in the way they talk about them: a man says, ostensibly praising his wife, “She was all for feminine rights and that sort of thing.” “Feminine”. But Kirsten doesn’t give us social satires. The fictional situations are recognizable and real, and they’re always being altered by the way the main character thinks or feels, or by someone doing something odd, strange, playful, whimsical, silly.

Philip keeps trying to come to grips with people’s real selves, but his gears are constantly slipping. This makes for magnificent bits of comedy, for instance when Phillip’s greengrocer comes in wanting a divorce, and an exchange ensues that is puzzling and exhausting for Philip, and hilarious for the reader. Let me quote a bit that’s a little after the section Kirsten intends to read, but from the same scene.

“This is my lawyer,” said the grocer. “I want a divorce.”

“What?” she said.

“You heard me,” he said.

“What lawyer?” she said.

She looked at Philip when she said it. She glanced at him as if he was just another passenger on a crowded train.

Kirsten has a lot of fun with this stuff. Frustrations and ludicrous mishaps may be trouble for the characters, but the reader is filled with affection for this anxious, gloomy, hopeful, experimenting man.

The Invisible Rider is a book that has a very strong feeling for its setting, particularly Island Bay and Wellington’s south coast, where the sea breathes, and the moon burns like Moloch, like a hungry God, where people look across, up, or down into other’s houses, and grand operas, farces, and pantomimes are played out on the sloped stages of hillsides. Landscape and cityscape are central to this book, which is about, among other things, encroachments. Encroachments and the self. The little wilderness of a section next door is bulldozed and developed. Ground is broken for a local supermarket, a project Philip had thought was “up for appeal”. Things change, and Philip starts mourning his children’s childhoods while they’re still quite small. He can see it all going. He can see it all coming. He doesn’t know quite what to do about it. Philip isn’t a sensible man, except in the old-fashioned sense. He’s alive to the moment and the possibilities of the moment, is a thoughtful person whose thoughts are reactive. Distressing events occur and Philip tries to resist. He puts his foot down on the road and stops the traffic, or tries to, but there is always someone shaking their head, and tapping their watch.

One meaning of the word “rider” is an addition or amendment to a document or testament. So, there’s this invisible rider, on his bike, a man making his own way, under his own power, disregarded and endangered by momentous, hurtling forces. Encroachments, the big cars that bloody own the road, the developer breaking ground immediately outside the kitchen window; something strange and death-dealing at the local pond; Christmas music ramping up in November at the local mall, and leaking in through all the seams of Philip’s flimsy office–there’s all this, road rage, headwinds, head lice, the silence between a man and his wife that pushes them to opposite ends of their marriage; the ghost of the dead mother who doesn’t console, or offer good advice, but just wafts in with her niggling commentary. How can a hero have boundaries if he can’t make himself seen? This funny, thoughtful book gives us all this in prose that is somehow condensed, like poetry, but prose with plenty of air in it. The narrative is a honeycomb holding good, glowing, flowing observation and invention. And a “rider”, an addition or amendment to the testament, does follow each story invisibly. We are shown what the protagonist notices, then, for the most part not articulated, but only implied, is this: If these things are noticed, what do we know? What we feel we now know after finishing each story–that’s Kirsten’s invisible rider.

I’m very proud to be launching this book which brings a wise and highly distinct new voice to New Zealand writing. So without further ceremony I will hand Kirsten and her invisible rider over to all you visible readers who will, I hope, carry the book from this place and bring it to the attention of many more readers not currently visible.

Thank you.