“Ah, there he was, standing in the blue, making a dome with his song.”

“Ah, there he was, standing in the blue, making a dome with his song.”

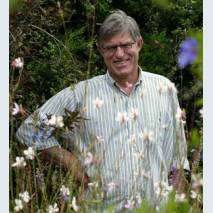

Skylark Lounge is my favourite of Nigel Cox’s books, though it is a close run thing with both Responsibility and his posthumous collection of essays, Phone Home Berlin.

Skylark Lounge appeared after a long gap in publication – Dirty Work, Nigel’s second novel, was published in 1987, Skylark Lounge in 2000. Between these novels are several abandoned works, (a tantalising excerpt of Academy can be found in the first issue of Sport).

Several things interest me about the bits of those abandoned books I was lucky enough to have read, and how I remember Nigel speaking about them. One thing is their relation to work by Ian Wedde appearing around that time. Nigel particularly admired Ian’s fiction. They both seemed interested in representing a cosmopolitan, down-at-heel, urban New Zealand, writing sensation and information dense depictions of our country as a place in which people lived in cities, inventing and enjoying themselves as human particles in the substance of neighbourhoods, as the regulars of pool halls, people with plausible street identities and monikers like Jimmy Ronk, Hairy John, and The Crazy Jap. The boarding house in Nigel’s Dirty Work is a microcosm of this New Zealand, and the novels between Dirty Work and Skylark Lounge seemed to want to try to widen the focus from that gritty urban outpost, to a whole city, or at least the citizens in one silo of a city.

I don’t know why those novels were abandoned. But what I have often suspected is that Nigel’s imagination was stymied or stifled by his determination to consider what would belong in the Kiwi gritty urban. In that kind of novel. And I feel that Nigel’s plans for those books may have demanded he set aside many of the things that went on to form the heart Skylight Lounge.

Skylark Lounge is a book by someone who didn’t want to write a “kind” of book; a book with a defensible territory. It is not coincidental that its protagonist’s name is Jack Grout. Grout isn’t what sticks tiles to a wall, it’s what joins the tiles, and seals those joins. Skylark Lounge doesn’t have a single setting – these mean streets – or a milieu. It has irises that open on its many scenes, a pool hall, a marriage bed, a back porch, a kitchen table in the Grout house, a tennis court, the surface of the moon, a Waiouru Motel. The novel’s gritty urban backs onto waste lots, and the waste lots abut wildernesses. The novel captures how, here, we can take very short steps from habitation to wilderness. It captures how short the distances are between dark places where we might be able to view all the visible stars. It is concerned with littleness, and immensity. With contingency and destiny. With the feeling that the things that happen to us were meant, that someone must have meant them, because they are so meaningful to us. It’s concerned with small places that are big enough for someone to have sufficiency of things to see and do to last a lifetime.

Skylark Lounge is a short novel, but an expansive one. It tackles time and space as both astronomical and anthropocentric. It has the long time in which feeling beings can lose their bodies, and the memories of their bodies, but also the slow time and contained space of a single human existence.

We are told that, as a child, Jack Grout nearly drowned in a river. And that, at the last moment, he was pulled out by a woman. He only remembers his unknown rescuer’s hand. It is typical of this book that the anonymous hand isn’t the subject of a novelistic plot. The story will not find and identify this woman. Jack only remembers. And remembering is the story. These sorts of moments are cumulative. And one of the climaxes to which the book builds is its protagonist’s episode of hallucinatory whole remembering, when Jack’s entire life is available to him – a life looked over and kept.

“I mean, I imagine you’ve gathered by now what I’m talking about. I’ve hinted around enough, I’ve been preparing you. It’s going to be an anticlimax now, you’re going to say, yeah, absolutely, Jack, you’re going to tell us you were abducted by aliens.”

One summer holiday in Pukerua Bay, on an unspecified number of nights, but often enough so that he came to expect it, nine-year-old Jack was abducted by aliens. Taken up, then put safely back in his bed in the bach his parents have borrowed. Returned happy and intact. And then it stopped, as if the aliens were no longer able find him when he wasn’t at Pukerua Bay. That is, until the novel’s present, when Jack is forty-six, and some months after he’s given up his salaried job and bought a pool hall, and also several months after completing a course of chemotherapy for the melanoma of which the doctors only ever found the secondary, but not the primary site. Jack’s aliens return, and this time he’s determined to examine them right back, to make sense of them, since the mystery of their attention has made nonsense of too much of his life—coming and going as they did, leaving him with memories and experiences for which he had no factual framework, nor a respectable cultural one either. Jack sets out to explain his history with the aliens, to himself, and whoever else might one day demand an explanation, like his worried and exasperated partner, Shelley, and their kids. The novel is, ostensibly, Jack Grout’s notes on aliens. His testimony, should something happen to him. Also, necessarily, it is an exploration of what these aliens might be interested in. “Why me?” Jack and the novel ask. It’s the “why me?” that, if we’re never moved to ask, in either complaint or wonder, means we haven’t yet suffered much, or that we’ve never felt blessed, chosen, singled out for a revelation.

What is great about this novel – and this is a novel with greatness – is that it takes Jack Grout’s solipsistic sense of singularity, and makes that sense serve a tender meditation on the beauty of human consciousness. And if that makes the novel sound esoteric, it is, it aims bravely at the big stuff, but always by getting close up to the particular, the mundane material world and it’s odd appearances, its contradictions, mind-blowing strangeness, and logic. For instance, Jack thinks about playing tennis, and what is means to him. His thinking is a hymn of praise.

“The squeaking of the shoes, and the sweating, the swearing, and the speaking of the scores. Fifteen love, thirty fifteen, thirty, forty, deuce – it’s a it’s such a mantra. Game set and match. The scoring system in tennis is a frame you can live within. There’s such certainty there, such logical progression. It’s the same with the court. Those beautiful white lines, the fat confidence of them. The regularity. Every court the same, with lines the same distance apart, the earth measured into identical plots all over the planet.”

Look at that. “Plots” as in stories, and graves. And that move from a particular court, to a world parcelled out into tennis courts.

There is Jack’s meditation on the top forty, his memory of how, during the week he spent painting a fence one summer of this teens, it seemed there was a connection between the laying of paint on a board, and a set of songs: “The next board produced ‘Kites’ by Simon Dupree and The Big Sound.” Nigel gets that sense of our living in the moment when we’re young, the moment and our bodies, and how that means that while we might know all kinds of people are listening to the same count down to number one, what is shared is also for us alone. We have been communicated with, formed, nourished, given a gift by the universe. The universe—all of it ours.

Jack’s aliens are often the occasion of these patient, pattern-and-meaning making musings. They came early to him and planted a seed of a way of seeing that had to be nurtured by silence and isolation, and a view from a very high place. But then they withdrew, and the plant they’d propagated grew into lostness and longing, leaving Jack to wonder; had the experience been psychotic rather than revelatory? Was he just a crazy person?

The novel imagines very well what being privy to the invisible feels like. It also does a bloody good job of making the all-seeing, disembodied, beneficent but withholding aliens seem completely believable. Its alien scenes take the reader step by natural step through extraordinary descriptions of exactingly rendered extraterrestrial encounters. Pop culture aliens are available to Jack – and often useful when he wants to describe what his aliens are not like, and what they don’t do. The novel doesn’t bother to pretend pop culture aliens don’t exist, it acknowledges all the things its readers know, then writes its own rules of invention.

Skylark Lounge is a novel about a middle-aged man having a crisis because the alien abductors of the most ecstatic period of his childhood return, bringing their alienating ecstasies. And it is about that. With gusto, and without coyness, the novel is about that. The reader squirms with Jack as he tries to avoid telling his family why he’s off – off by himself, off at odd hours, off in his behaviour. And it cleverly incorporates into the story why Jack’s family at first offers him such latitude with his crisis. He’s recently had a brush with cancer, fruitless scans, and a course of chemo. By putting the cancer alongside the aliens as what might be going on with Jack, Nigel avoids the possibility that the metaphorical scope of his book will be reduced to the aliens representing cancer. I have heard Skylark Lounge discussed that way, and I remember that the first time I read it, with Nigel’s melanoma’s first appearance so fresh in my mind, I was happy to accept the idea that the aliens were a metaphor for cancer (as well as being real science fiction) and that this was a way Nigel had found to write about his illness – as if he wasn’t actually in parts of the book straightforwardly writing about his illness. As if cancer was at the heart of the book, rather than being just one of the book’s occasions of contemplation.

I didn’t however, in my early reading, reduce the book to this interpretation. I loved how the aliens and their passionate curiosity threw their human subject into a storm of memory and reverie. I thought, “This author has had a brush with mortality and is mapping the great constellations of his emotional life, the river, the rescuer’s hand, the fence boards, the songs, the tennis courts, and pool tables and back steps and twisting scoria gullies of the desert road.”

Reading the novel now, at fifty-seven, a year older than Nigel was when he died, I can still see the aliens as aliens – as character and plot. And I can still see them is something of a metaphor for cancer. Or for the interruption of life by fear of death, which throws us back on life.

But now I can see whole new strata of meanings, and a book I always admired and considered intellectually and emotionally deep has flowered further in my understanding.

It seems to me now that Skylark Lounge is also a book written by someone who had, at some points in his life, a very real fear of losing his mind. I recognise this partly because between 2000, when I first read the novel, and 2006 when he died, I learned a lot more about Nigel. I also recognise this from my own life, from observing and thinking about my older sister’s difficulties, and from some sketchy times I experienced (and determinedly ignored). These things pass, thank goodness. Coincidences stop communicating insights specially to us. All the patterns return to being simply pleasing, not significant. The world won’t be saved by any one of us working it out in their mind. That isn’t something we have to do. Phew. A person can relax just have thoughts and dreams – and stop doing the world’s or God’s work, late at night, with the river of our whole lives streaming through our heads, in a channel the full moon has made. Phew. But, then again, we are no longer ecstatic, no longer taken up and shown the whole world. We not chosen, nothing is made specially for us, and there is nothing that we alone can do.

Skylark Lounge captures both the terror of that state of mind, and the grief at its passing. It manages to do this with more care and deliberation, and more spirit, than anything else I’ve read.

Another thought I had about Jack Grout’s having been press-ganged into the job of revealing human life to aliens, and his pressing need to understand what all that actually means, is that this is the writing life. The fiction-writing life. Jack’s aliens make him go off on his own, make him secretive, vague and cold to his friends and family. Jack’s aliens are an enemy of family life, and the reliably ticking-over everyday. They put thoughts into Jack’s head that no one else can see or hear. They torture him with immanence, with things that have to be solved, with the tantalising, unsettled shimmer of a great pattern. Jack Grout’s aliens are isolating and marvellous, and they do his head in. They are the writing life. They pass through – like novels – leaving him to say, “I’m back. Sorry I was absent. I’ve had enough out, please take me back in.”