I will begin with withered leaves blowing through an empty fairground, tent canvas gulping and gulping, and the seats on the dark Ferris wheel creaking, rocked by ghostly fairgoers. By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes.

I will begin with withered leaves blowing through an empty fairground, tent canvas gulping and gulping, and the seats on the dark Ferris wheel creaking, rocked by ghostly fairgoers. By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes.

My first encounter with horror was a book of ghost stories I sneaked from the bookcase in my Uncle Keith’s bach, and a story which kept me feverishly awake as one of its protagonists was also up all night, disturbed by whispering, a breath blowing on his ear through ‘the chink in the wall’. I write ‘his bed’, but want to write ‘the bed’, smudging the story’s shades into my own, because, more than any other kind of reading, ghost stories work that way. They chase you when you’re alone and undefended, as we all are when worn out by wide-eyed, wakeful terror, when we’re only eight years old, in the top bunk, and the hot lights of the poultry farm hatchery on the other side of the hedge are crawling on the ceiling and bedclothes like larvae of daylight, while dawn is still hours away. I wish I could recall the title of that book. An omnibus of ghost stories. Omnibuses were things you got on innocently and which carried you off along some dark road with tight corners and bluffs where buses shouldn’t go, in a countryside of stark grazed hillsides with black macrocarpa shelter-belts.

Close to that time there was also Doctor Who, and the Macra Terror, a crablike monster lurking in ‘the old shaft’, waving its claws and blinking its bulbous eyes. (The brainwashed inhabitants of the planetary resort were almost as scary as the monster, with their crisp, positive voices and satin bandmaster suits.)

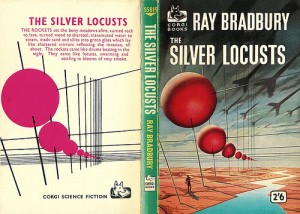

At eleven I encountered Ray Bradbury. He could be very scary – it was his haunted fairground. And even when things turned out all right in his stories because the boy whom no one would believe was finally able to convince someone that there were screams coming from the empty lot. Even then, when they dug up the woman in the box, and she was saved, the boy vindicated, and the slighting adults chastened, you were still left wondering what it was like for that woman afterwards, and how would she feel if she woke up with her face two feet from the ceiling in the top bunk?

At eleven I encountered Ray Bradbury. He could be very scary – it was his haunted fairground. And even when things turned out all right in his stories because the boy whom no one would believe was finally able to convince someone that there were screams coming from the empty lot. Even then, when they dug up the woman in the box, and she was saved, the boy vindicated, and the slighting adults chastened, you were still left wondering what it was like for that woman afterwards, and how would she feel if she woke up with her face two feet from the ceiling in the top bunk?

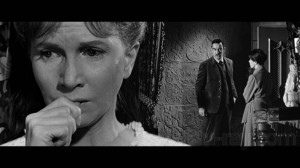

So, there was Bradbury with his mists and autumn and leaves that weren’t leaves blowing through ruined Martian cities. There was Disney’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, the reliably frightening Doctor Who, and all the other omnibuses and anthologies – Irish, German, Latvian, Japanese ghost stories. And there was Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte and Robert Wise’s film of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting. (Only my inconsistently prohibitive parents would have thought to exile Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination to the top shelf of the hall cupboard, and let me watch The Haunting.)

I’ll jump a few years then, to my teens, and The Legend of Hell House. After I’d seen the film Dad pointed me to Richard Matheson’s novel on which the film was based. Dad admired Matheson the screenwriter, especially the beautiful transcendence of the final monologue in The Incredible Shrinking Man. But Dad was contrary, he loved science fiction and despised fantasy. For him horror was in an uncomfortable territory between the two, and the virtue of Hell House was that it turned out that the evil guru Belasco’s ghost had an electro-magnetic rather than spiritual existence, and that his spirit survived with his enthroned, mummified form in a lead-lined room at the heart of the house. The scientist investigating the haunting was gruesomely dead, but vindicated. There was a charge for me too in that, something that sat beside Dad’s approved of ‘science in the fiction’, and that was the spectacle of people negotiating their fear with thought and problem solving. It was meaningful to me not because it made these victims of the supernatural evil more hopeful, but because it made them more human – more valuable, more energetically alive, and more comprehensively doomed in the face of the story’s malignancy.

I’ll jump a few years then, to my teens, and The Legend of Hell House. After I’d seen the film Dad pointed me to Richard Matheson’s novel on which the film was based. Dad admired Matheson the screenwriter, especially the beautiful transcendence of the final monologue in The Incredible Shrinking Man. But Dad was contrary, he loved science fiction and despised fantasy. For him horror was in an uncomfortable territory between the two, and the virtue of Hell House was that it turned out that the evil guru Belasco’s ghost had an electro-magnetic rather than spiritual existence, and that his spirit survived with his enthroned, mummified form in a lead-lined room at the heart of the house. The scientist investigating the haunting was gruesomely dead, but vindicated. There was a charge for me too in that, something that sat beside Dad’s approved of ‘science in the fiction’, and that was the spectacle of people negotiating their fear with thought and problem solving. It was meaningful to me not because it made these victims of the supernatural evil more hopeful, but because it made them more human – more valuable, more energetically alive, and more comprehensively doomed in the face of the story’s malignancy.

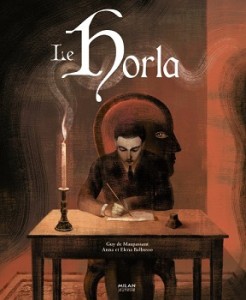

In my teens I especially loved stories where someone waits in dread. M R James’s ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to Ye Laddie’. Bram Stoker’s ‘The Judge’s House’. And, most of all, Guy de Maupassant’s ‘The Horla’ – one of those ‘This manuscript was discovered after the death of…’ stories, of which The Blair Witch Project is a direct descendent. No one is left alive to tell the tale, except it is already told, there’s this mad journal, this mad film, and what are we to make of it?

The other given of horror, besides menace, is madness. Not so much madness from the outside: the distressing spectacle of insanity, of madness as a problem to the sane. (Though I will always regard Lucy Westernra’s simultaneous physical failure and sustaining mania, and her friends’ and parents’ misery, as the most terrifying things in Dracula.) No – it’s the loneliness of madness that is at the heart of horror. Think of the demented hero of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, screaming ‘They’re already here!’ at people on the highway, peering with fear into every face, in deep doubt about who can be trusted and who cannot, who is human and who is not. Think of ‘The Horla’, a story which takes the form of the journal of a man who went mad and burned his house down, killing all his servants, because he had come to feel, over a series of darkening days, that he was never alone, even in an empty room. To feel that a presence was ghosting his steps, reading the pages of his journal when his back was turned, drinking the milk on his bedside table, bowing its head beside his to smell a rose, enjoying his life as he was, day by day, less able to. I read ‘The Horla’ when I was fourteen and understood why I was frightened by this invisible stalker with unknown intentions towards the story’s protagonist. I was scared of what scared him. But, without fully understanding why, I was also deeply frightened by the protagonist’s dread itself, by the way in which his life became strange to him, the tale’s stain of depression and slow estrangement from self. (Maupassant’s story was written under the influence of a mood of alienation from things – the beginning of a mental dissolution from the effects of syphilis on the brain.)

The other given of horror, besides menace, is madness. Not so much madness from the outside: the distressing spectacle of insanity, of madness as a problem to the sane. (Though I will always regard Lucy Westernra’s simultaneous physical failure and sustaining mania, and her friends’ and parents’ misery, as the most terrifying things in Dracula.) No – it’s the loneliness of madness that is at the heart of horror. Think of the demented hero of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, screaming ‘They’re already here!’ at people on the highway, peering with fear into every face, in deep doubt about who can be trusted and who cannot, who is human and who is not. Think of ‘The Horla’, a story which takes the form of the journal of a man who went mad and burned his house down, killing all his servants, because he had come to feel, over a series of darkening days, that he was never alone, even in an empty room. To feel that a presence was ghosting his steps, reading the pages of his journal when his back was turned, drinking the milk on his bedside table, bowing its head beside his to smell a rose, enjoying his life as he was, day by day, less able to. I read ‘The Horla’ when I was fourteen and understood why I was frightened by this invisible stalker with unknown intentions towards the story’s protagonist. I was scared of what scared him. But, without fully understanding why, I was also deeply frightened by the protagonist’s dread itself, by the way in which his life became strange to him, the tale’s stain of depression and slow estrangement from self. (Maupassant’s story was written under the influence of a mood of alienation from things – the beginning of a mental dissolution from the effects of syphilis on the brain.)

This is my history with horror. All these things taken together. A vortex formed by the rattling wind from Ray Bradbury’s haunted fairground, which spins through it all. A vortex that takes in the Macra Terror; sweet Charlotte and her axe; Roderick Usher and Emeric Belasco; rapt, wrongheaded, ghost-haunting Eleanor Vance; the judge’s house, dead Martians, people buried alive, and an invisible something bending the steel stairs of Forbidden Planet‘s spaceship as it climbs clandestinely inside. A vortex takes in the horla, and every other monstrosity who, for whatever inscrutable reason, chooses to put its mark on you. Every easily offended, grimly playful monster that comes to show you the consequences of your hapless transgressions. Every monster – hidebound and punitive – enacting revenges from old stories that are nothing to do with who their victims really are. That kind of monster, or one that is sad and deathly, lonely and cold, like Bradbury’s Martian ghosts, or Tove Jansson’s Groke – the creature who comes in her halo of frost, fixes her pale, hungry eyes on the lamp and shuffles nearer, ever nearer, until that lamp goes out.

This piece first appeared on the Booknotes Unbound website