I first read The Master and Margarita when I came across it in the Tawa College library. It must have gone deep into me because I didn’t realise until I reread it many years later how much it had influenced me.

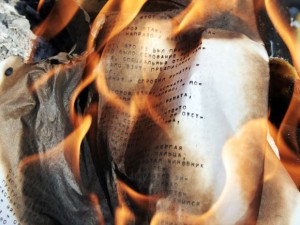

It comes at its main story by two debonair flanking movements. The devil and his retinue appear in Moscow in the slightest of disguises, and go largely unrecognised because vain members of Masslit – the writers union – and venal theatre managers, and rapacious, luxury-starved Muscovites, are all too busy being themselves, thus collaborating with the devil’s obscure mission – which might simply be to host his annual slap-up party. It is a book in which a novelist is driven mad by despair, and burns the manuscript of his book about which editors and critics have only wanted to know why he, ‘a Muscovite in this day and age’, wrote a novel ‘on such a curious subject’. The Master’s novel concerns Pontius Pilate. The reader encounters the novel’s story of Pilate in chapter two, around 150 pages before the man writing the Pilate novel – the Master – makes his appearance. We don’t know why we’re being told about Pilate. We do know it’s riveting. The Pilate chapters, which appear at intervals in the novel, are measured, realist, vivid. So is the ostensibly most fantastical chapter, in which the Master’s lover, Margarita, turns into a witch and flies around the city causing mayhem, then travels upriver on a senses-saturating summer night. Margarita’s every witchy move is real, concrete, logical. But the novel also has scenes in a confined commonplace present: the offices of a theatre manager, where a couple of worldly men get excited trying to work out why someone would be pretending to be the theatre treasurer and claiming to have been magically transported to Yalta. They discuss a series of telegrams from someone in Yalta. And the telegrams keep arriving, carried by the same girl from the post office, giving the two guys just enough to react to each message before she walks in with the next. It plays like a stage farce.

It is this melting, shimmering quality that I most love. The novel manages to be is stately and tragic – in Pilate’s and the love story – while also being antic and flamboyant. It thrives on madness and mixedness, but the net result is a strong sense of mission which I suppose could be distilled down to this idea: How easy it is for cruel and implacable individuals to create a world in which it is almost impossible for decent people to do good. Just that idea, with myriad proofs. It’s a novel in which almost all the heroes are compromised or defeated, and have given up on civilisation to save their souls.

When I read The Master and Margarita at sixteen I thought it was the strangest and most astonishing book. I’ve read it twice since. It has changed and deepened, both with my accumulated life and with history, and is still the strangest and wildest, and wisest, book I’ve read. And the next time someone asks me dubiously about my use of fantasy I will wish that Woland would dispatch the black cat Behemoth to smack them in the ear.