Between 1954 and 56 my father was a guide at the Hermitage, in the Southern Alps. I was brought up with Sefton and Sebastopol, shale and serracs. And with dad’s ice axe, which hung in the garden shed in Pomare, then the basement workshop in Wadestown, and finally in the garage in Paremata.

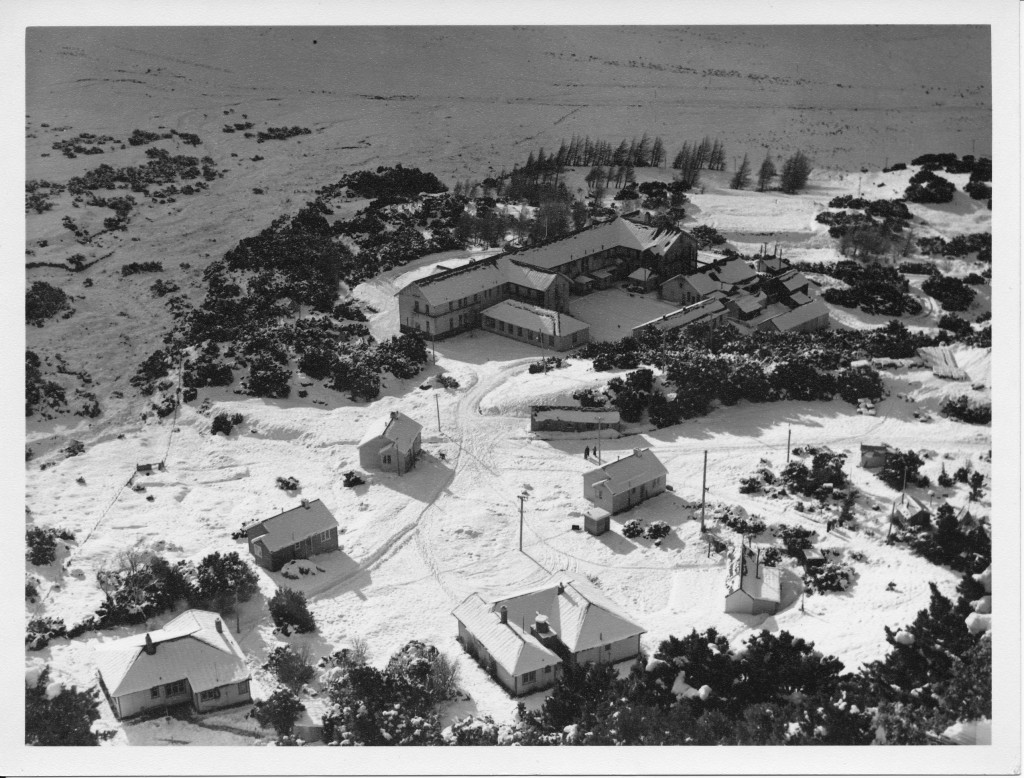

The Hermitage, which the Department of Tourism sold as: “Thousands of feet above worry level.” A little clutch of buildings set down in what one British journalist called a quarry. An Alpine Valley, with tussock, and heaps–not of slag, but shale, the gizzard stones of glaciers.

The Hermitage, which the Department of Tourism sold as: “Thousands of feet above worry level.” A little clutch of buildings set down in what one British journalist called a quarry. An Alpine Valley, with tussock, and heaps–not of slag, but shale, the gizzard stones of glaciers. This is the Ball Hutt bus. Winter was ski season and the guides would open the ski room, check all the bindings, shelac the skis, three coats each, and service the ski tow engine.

This is the Ball Hutt bus. Winter was ski season and the guides would open the ski room, check all the bindings, shelac the skis, three coats each, and service the ski tow engine.

When the snow was deep they’d move supplies up to the hut by tractor, on a road that in one section ran along the top of the moraine, with a big drop either side. They’d pick up supplies dumped by the bus at Husky Camp. In the worst weather they’d only go when they ran out of beer.

When the snow was deep they’d move supplies up to the hut by tractor, on a road that in one section ran along the top of the moraine, with a big drop either side. They’d pick up supplies dumped by the bus at Husky Camp. In the worst weather they’d only go when they ran out of beer.

The guides thought the tractor trip so hair-raising they decided to do fewer, and carry more. They built a sledge, and only then ran their it past Mick Bowie, the head guide. Mick was famously inscrutable. He had a grunt which could mean he was a)disbelieving, b)deeply offended, c)at a loss for words d) grudgingly giving in. Mick grunted, but the sledge was a bust.

The guides thought the tractor trip so hair-raising they decided to do fewer, and carry more. They built a sledge, and only then ran their it past Mick Bowie, the head guide. Mick was famously inscrutable. He had a grunt which could mean he was a)disbelieving, b)deeply offended, c)at a loss for words d) grudgingly giving in. Mick grunted, but the sledge was a bust.

This is Ball Hut. The caption written in Dad’s hand on the back of the photo is, “My home most of the time.”

The rest of the winter the guides strapped their skis on their backs and trekked off to mend huts. Here’s Dad fixing a hut roof.

The rest of the winter the guides strapped their skis on their backs and trekked off to mend huts. Here’s Dad fixing a hut roof.

Dad loved the mountains so much that he bought pastels and started trying to capture them. He tossed his failed pictures of the perfectly round rainbow-hued cloud he’d seen. “Unbelievable” he said. “All it lacked was a little green man climbing out of it.” This he kept.

Dad loved the mountains so much that he bought pastels and started trying to capture them. He tossed his failed pictures of the perfectly round rainbow-hued cloud he’d seen. “Unbelievable” he said. “All it lacked was a little green man climbing out of it.” This he kept.

Summer brought tourists. The guys in swannies are the guides. The tallest is Phil Boswell about whom I know only this; that he could suck up a whole plate of jelly in one go with a sound like a cow pulling its leg out of a bog.

Summer brought tourists. The guys in swannies are the guides. The tallest is Phil Boswell about whom I know only this; that he could suck up a whole plate of jelly in one go with a sound like a cow pulling its leg out of a bog.

Dad blew a hernia racing up a hill with a crate of beer. He spent three weeks in hospital in Timaru. The surgeon said to him, “It this operation succeeds you can keep on guiding. If not you can do something else.”

Dad blew a hernia racing up a hill with a crate of beer. He spent three weeks in hospital in Timaru. The surgeon said to him, “It this operation succeeds you can keep on guiding. If not you can do something else.”

“What else?” Dad thought. If he left the Alps he believed some part of him would die, change, vanish.

When he came back he was on light duties. He’d take tourists for an amble down the moraine onto the white ice of the Tasman, and they’d sigh with wonder.

When he came back he was on light duties. He’d take tourists for an amble down the moraine onto the white ice of the Tasman, and they’d sigh with wonder.

They’d go into an ice cave, or he’d let them toss rocks down a moulin to hear the distant splash in the blue depths of the glacier. When I was eleven he took me onto the Tasman, and we did those things.

They’d go into an ice cave, or he’d let them toss rocks down a moulin to hear the distant splash in the blue depths of the glacier. When I was eleven he took me onto the Tasman, and we did those things.

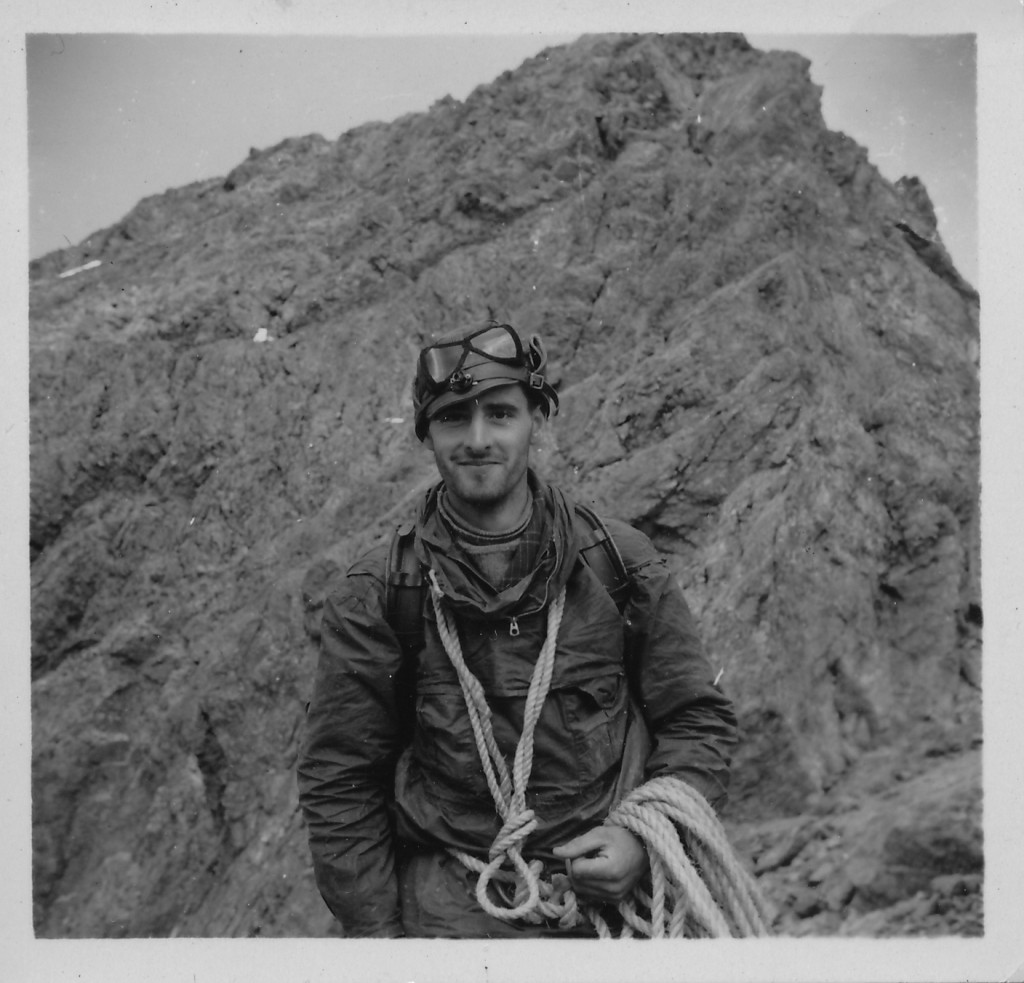

In summer serious climbers set off up mountains. Here’s Dad, about to break through a cornice onto a ridge.

In summer serious climbers set off up mountains. Here’s Dad, about to break through a cornice onto a ridge.

Once he fell into a crevasse, losing the white ski cap Mum had knitted for him, and his self-possession. He was saved by his ice axe and another guide’s belay. But it took him four hours to climb out.

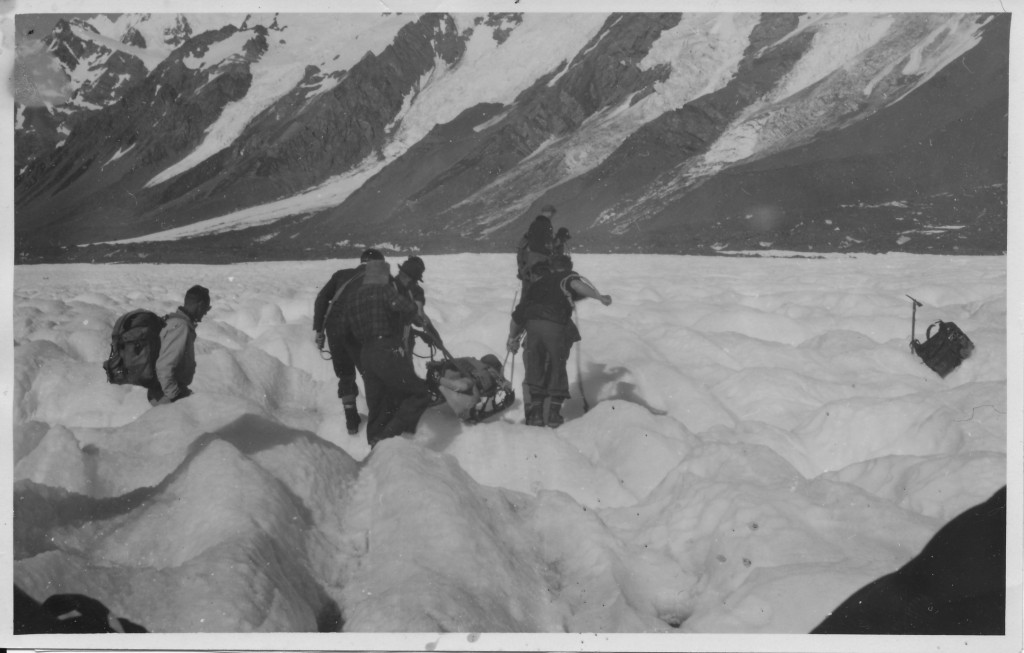

Alpine rescue. Tasman Saddle, 1954. Dad is at the back, with a hat. The woman in the stretcher had slipped on the ice and broken her leg.

Alpine rescue. Tasman Saddle, 1954. Dad is at the back, with a hat. The woman in the stretcher had slipped on the ice and broken her leg.

In February 1955 Dad married. Mum and he moved into Sealy cottage. Mum loved the white Rainer cherry trees around the Hermitage, the black Alpine butterflies, the white Alpine grasshoppers. But she didn’t like the winter, when the kea would come and swing upside down from her frozen washing.

In February 1955 Dad married. Mum and he moved into Sealy cottage. Mum loved the white Rainer cherry trees around the Hermitage, the black Alpine butterflies, the white Alpine grasshoppers. But she didn’t like the winter, when the kea would come and swing upside down from her frozen washing.

Mum is on the left.

This is dad with Harry Wrigley on the day he first landed his prototype skiplane. It was a great success and there were many drop offs. Wrigley used to read his newspaper until the plane was right between the mountains, then he’d pass it back to another passenger, and open his window to pull the lever that made the wheels retract through slots in the skis.

This is dad with Harry Wrigley on the day he first landed his prototype skiplane. It was a great success and there were many drop offs. Wrigley used to read his newspaper until the plane was right between the mountains, then he’d pass it back to another passenger, and open his window to pull the lever that made the wheels retract through slots in the skis.

So, there was a baby on the way, no medical facilities, no other children, no promise of a school, and a doubtful future in guiding. The tourist department already had guides eradicating stoats, and cutting down the Rainer cherries.

So, there was a baby on the way, no medical facilities, no other children, no promise of a school, and a doubtful future in guiding. The tourist department already had guides eradicating stoats, and cutting down the Rainer cherries.

When Dad was depressed, I’d imagine him in a snow cave. He took this photo when he and some friends were snowed in for six days on the Franz Josef Neve. He was probably quite content. He loved to keep moving–but he always carried a book, and he’d write poems on the end papers.

When Dad was depressed, I’d imagine him in a snow cave. He took this photo when he and some friends were snowed in for six days on the Franz Josef Neve. He was probably quite content. He loved to keep moving–but he always carried a book, and he’d write poems on the end papers.

Here he is balancing on Turner’s Rock, above a two thousand foot drop. Never afraid of falling. The only time he had a near miss was when his jersey got caught on a nail in some scrap timber he was tossing onto the dump far below Malte Brun.

Here he is balancing on Turner’s Rock, above a two thousand foot drop. Never afraid of falling. The only time he had a near miss was when his jersey got caught on a nail in some scrap timber he was tossing onto the dump far below Malte Brun.

See the cigarette in his mouth? That’s what eventually got him.